In the windswept plateau of South Eastern Spain, where the soil had been eroding, where desertification had been threateninghad the area, and where the community had been struggling with the exodus of young people, La Junquera farm, has been pioneering regenerative methods, and spearheading the activation and restoration of the local watershed. Its been hosting educational workshops for neighboring farmers, and its ways have gradually osmosized into the surrounding area. I had the pleasure of interviewing Slyvia Quarta, an articulate and action-oriented academic-turned-farmer, who works at La Junquera farm, running a regenerative educational program there called Camp Altiplano. Her bio reads “I love having calluses on my hands, taking a hot bath, having a beer at the Topares bar, and being alone on the farm when everyone leaves.”

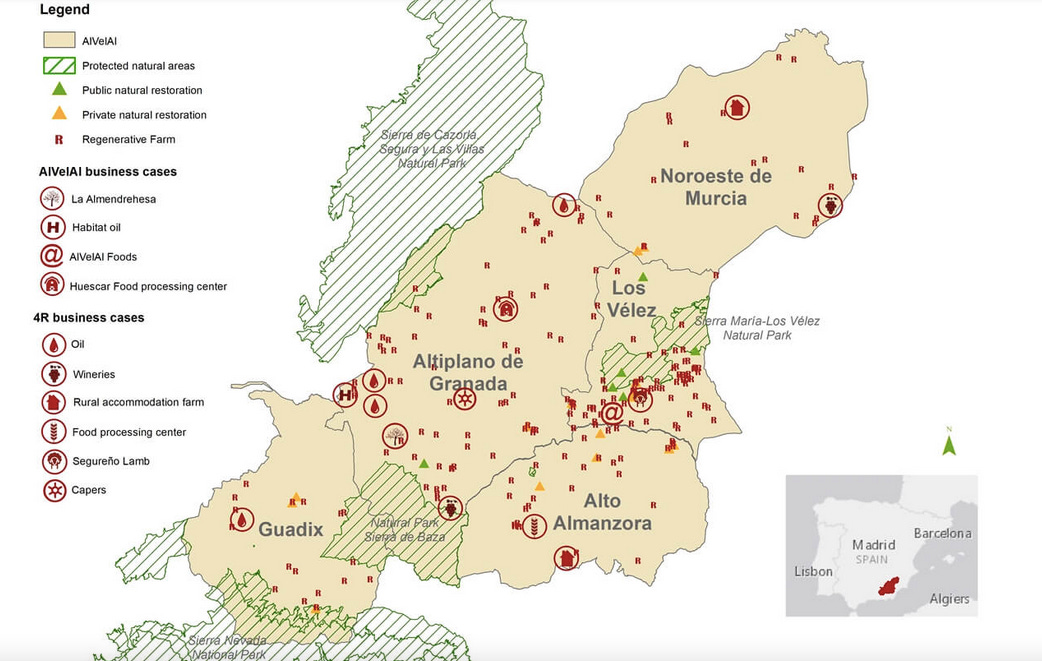

La Junquera farm is part of a larger Alvelal multistakeholder network, that brings together hundreds of farmers, local businesses and scientists working together for the prosperity of the region. They came together in 2014, and created a 20 year strategic roadmap that works to build community and shift the extractive sector into the regenerative sector. It has regenerated much over the past decade, and in the future aims to restore an ambitious 100,000 hectares. Alvelal’s success provides a model which other large scale land restoration projects in Iberia (and there are number of these), as well as around the world, can follow.

Alvelal writes on its website “We intend to mobilize local society to transmit the vision that a self-sufficient, dignified region, full of life and prosperity, is possible. A young and revitalized territory that knows and values its resources, with a professionalized ecological agricultural sector and with business opportunities and restorative initiatives for society, the economy and the territory. This is why we work on the restoration of agricultural properties with degraded or eroded soils, through regenerative soil and landscape agricultural techniques. We offer training workshops and technical advice, thus guaranteeing an open and supportive transmission of knowledge. We promote marketing plans for indigenous organic products with great quality differentiated by their productive management. Above all, we want to help all those initiatives that defend the recovery of the landscape, culture and economy of our territory. Likewise, we are committed to the restoration of biological corridors to promote the conservation of biodiversity; activating and energizing local networks around landscape restoration.”

Here’s a segment of the interview with Sylvia Quarta, (edited for clarity and brevity):

Silvia: I'm currently at La Junquera, a large regenerative farm in southern Spain. It's a 1,000-acre farm, and we’re part of a larger landscape restoration project through Alvelal, a regenerative agricultural association that connects a vast landscape of 100,000 acres here in southern Spain, spanning different provinces: Murcia, Almería, and Granada. It started around 10 years ago, and their goal is basically to restore the landscape—not just in terms of land and nature but also through social restoration, creating jobs, improving the economy, and developing a patchwork landscape with natural areas as well as great regenerative farms and inspiring places. We mainly follow the Four Returns framework, which is part of the Commonland work focused on returning natural capital, economic capital, inspiration, and social capital.

[from La Junquera’s website]

Alpha: Cool, I'm excited to dive in with you to explore more about your farm and the larger network it’s part of and how that all came together to restore 100,000 acres in southeastern Spain. But first, let’s talk about you. How did you get involved in the regenerative field?

Silvia: I’m from northern Italy, from a fairly urban area. I grew up half an hour away from Milan, a big city. At some point, I decided to study environmental sciences and went to the Netherlands. That changed a lot for me because I did my internship and my thesis on farming-related issues. I worked with indigenous communities in the Andes, and I experienced the whole world of agroforestry, organic agriculture, and permaculture. It really opened up for me, and I realized I wanted to do much more than just research. I ended up in a project in southern Spain where I worked as a volunteer for over a year on dryland restoration—learning about and restoring native species, maintaining a nursery of native varieties, planting in the desert, and having a forest garden.

After that, I worked a bit at Wageningen University and coordinated excursions for the land and water management program in Portugal. We traveled across the country looking at issues related to large irrigation schemes and syndromic systems, giving students and ourselves a feel for the contrasts in land and water management in the desert.

Eventually, I ended up here at Campo Altiplano; it’s the first ecosystem restoration community created by John D. Liu, who is the founder of the whole movement. This camp started in 2017 at La Junquera, and I came a couple of years later. So for the past five years, I’ve been managing a five-acre plot that we’ve transformed from a cereal field into a mixed regenerative agroforestry permaculture system, working with volunteers and the community.

Alpha: Can you tell us a little bit about the landscape there?

Silvia: You can’t hear it, but it’s crazy windy outside today! It’s quite typical because we’re on a plateau at 1,100 meters elevation. It’s Mediterranean since we’re only an hour away from the coast in the Murcia region, but being high up means we have a vast landscape with broad horizons, which can be quite monotonous. We get an average of 350 millimeters (14 inches) of rainfall per year, but in the last 12 months, we’ve had less than 100. It rained 30 millimeters last Saturday, which was basically the first rainfall we’ve had in a year. It’s been horrible winters; usually, it rains from October to April, but that hasn’t been the case in recent years. Winter can get really cold, and it can even snow, but it also gets super hot in the summer, with temperatures reaching up to 40 degrees Celsius (104 F). So there are huge temperature fluctuations throughout the year and even throughout the day.

Most of the land around here is farmland—cereal land, mostly—but there are also more almond trees now. Because of our climate, it’s not easy to grow a wide variety of crops. Traditionally, it was mainly cereals, but now there are more almond trees and pistachio trees being grown. There’s a part of the valley where we’re located that is irrigated and increasingly hosting intensive vegetable production systems. Companies from other places rent out the land at very high prices and manage to have three cycles of lettuce growing in one season, which they then export to Germany, for example. The aquifers are suffering quite a lot—our spring, which is our drinking water, has gone down from 20 liters per second, about 10 years ago, to just 4 liters per second now. Nitrates are contaminating the water. It’s a beautiful landscape, but it faces many challenges; it’s highly exploited and is also depopulating quite quickly.

Alpha: A lot of the soil has been washed away, right? There’s not much soil left because of the winds and how it can’t hold onto it in the landscape.

Silvia: Exactly. Because of conventional farming and plowing everywhere, the soil is bare. When it rains, like now after three years of basically nothing, just 30 millimeters, a lot of soil gets washed away. That really shouldn’t happen, but everything is so dry and destroyed that it does.

Alpha: And the other part is that the aquifers are being drained because that’s what the farmers are using. But that means the trees can’t get as much water, right?

Silvia: Yes. It’s a vicious cycle—the water levels are dropping, which means there’s less water available for everything else. The biological flow in the river has decreased, and some parts of the river don’t exist anymore because they’ve been drained for farming.

Alpha: So how did the La Junquera farm get started? Was there a vision behind it initially?

Silvia: This is a family farm that has belonged to the same family since the 1800s. It was originally bought for the production of hemp and as part of grass, which is this rough grass that grows in highlands. It’s pretty sturdy, and you can weave things with it, like ropes and baskets. When hemp production declined, they turned to cereals. About 10 or 12 years ago, Alfonso, the youngest son of this family, came here to take over management. He was around 23 or 24 at the time. The family had someone managing the farm while they lived a few hours away, but he decided to come here and gradually took over the whole management.

His goal was to restore diversity and biodiversity in the soil since they noticed production was declining and the farm wasn’t doing well. They were completely dependent on one crop, so they started introducing different crops. They added almond and pistachio trees, as well as aromatic herbs like lavender and sage for essential oils. A lot of effort went into water retention and biodiversity work. We’ve planted more than 40,000 trees and bushes of native species for reforestation, both in natural areas and along field edges. Basically, the vision is to create a more resilient, beautiful, diverse, and healthier farm that improves soil health and biodiversity while still producing.

Alpha: And the ponds that you built, are they allowed to seep into the ground, or are they more for storing water?

Silvia: No, they're pretty much all clay around here, or at least for large parts. They waterproof themselves quite easily. The idea is that they're meant to provide some water for wildlife—frogs, and whoever wants to use the water—but also to slow down the water and let it infiltrate. Usually, the ponds just handle the largest water runoff, while the swales can be used where the slopes are a bit softer and there's less runoff.

Alpha: Can you irrigate the crops from the pond water?

Silvia: No, that’s not really the idea. Usually, you need the most water in summer when there’s probably the least water in the pond. Most of them are seasonal ponds. We had a few that had water all year round, but not this year. Even those dried up, so the groundwater level probably went down a bit because of the drought. We did try a temporary pump to water part of the land with the pond water, but it just didn’t make much sense because, in summer, the water level was lower, plus it has high salinity because of the area's geology. In the end, yeah, it’s just not practical.

Alpha: So what large-scale changes have happened as a result of this farm?

Silvia: The large-scale change is what we’re trying to get into right now, which is, after all these years of working on this farm, we want to address the water issue and connect with the place around us.

We’re focusing on a whole valley restoration project. As I mentioned, we have a spring on our land, which is our drinking water, and that spring is going down. It’s the beginning of a river which runs for about 80 kilometers and then ends up in a dam, and that’s it.

In those 80 kilometers, it's been disappearing. So we’re focusing on the first half of the catchment of the whole river, which is 30,000 hectares. What we want to do in this 30,000 hectares is involve the whole community—farmers, the local municipality—and change the way farming happens.

We’ve already started organizing training for farmers. We have a project funded together with the municipality to talk about soil literacy with people here and come up with an agreement on actions we’ll take together to protect the soil.

We’re working with schools around here and want to restore the cultural connection of people to this valley and this river. Because it's been such a harsh few years, people are more interested in what's happening on this farm. So I think this is the large-scale change we’re aiming for. Plus, the farm is also offering consultancy and management for other farms in the area

Alpha: So the idea is to get a lot of these farms upstream to build up their soil so that the water can infiltrate and take a little longer to reach the river, allowing it to run into the dry season more.

Silvia: Yeah, we want to restore a broken cycle. We want to create some space for biodiversity around the river, which is absolutely not respected at the moment. We want people to experiment and try out local varieties of crops that are being forgotten. Our vision is that in 20 years, this place will be much greener, with a lot more crop variety, products coming from this area, and a whole supply chain happening here. We want to create processing and added value for these products.

There should be more people, especially young people, because the population around here is disappearing. All the young kids want to leave, and they know that the only way to stay here is to work in agriculture, but they don’t necessarily want to do that. So we need to make this place more alive, thriving, and self-sustaining.

Alpha: So this is your larger vision—a 20-year plan that you guys are working on with all the different stakeholders. How did this begin? How did you come up with this larger vision of bringing a lot of different stakeholders together?

Silvia: I think it first happened because, at different points in time, we’ve all been driving through this valley I’m talking about. There’s the main road we usually take, but there’s also this side road that goes along the river, where you see abandoned farm buildings and really nice areas. The land is farmed, but the buildings are abandoned, and all of us—people living and working here—have been thinking, “It would be so nice to have these places restored and have more people living there with more projects like this one.”

I think we were all thinking that until we started voicing it and talking about it. That’s one part, the dreamy bit. Then there’s the reality check, which is that at one point along the river, there’s another farm that the same people own. Ten years ago, the river’s water used to reach this farm, and now it doesn’t.

So it’s also a very real change in the landscape and the land. Alfonso and Yannick, his wife, have been living here for six or eight years. She founded the Regeneration Academy, which translates research and complex knowledge into easily accessible knowledge for farmers. They also work with students doing research on the land and train farmers. So they bring education to regenerative agriculture in a more accessible way.

[from video on La Junquera’s website]

They have two kids, four and two years old, and I think that’s a huge reason for doing something about it. For all of us, it’s the realization that yes, we’re working on a farm and making an impact, but it’s limited. So how do we make a larger impact?

Alpha: It seems like one of the reasons is that the water on each farm is impacted by the overall actions you take in the whole watershed. So to improve the water system, you need to get a larger group of people working together—not just your own farm. Another thing is having a community of peers; it’s nice to have local people working on it together and supporting each other.

So you developed this regenerative school. Was it difficult? Sometimes farmers don’t want to convert from the ways they’re farming. How hard was it to show them this other way of farming?

Silvia: I think we’re not really trying to convert them. As you said, it doesn’t work if you go to someone and tell them they’re doing it wrong and should do it differently. That’s why we focused mainly on our farm first. Our goal was to restore this farm and work differently here, but we also wanted to offer an example.

When we offer training, people can come here and see what we do. More and more people are interested, especially in these tough years when there hasn’t been any cereal harvest for the past three years. Our farm has other crops, and they think, “Oh, maybe these people are doing something right.” The harshness of this period has made more people realize there’s something interesting happening here.

We just offer alternatives and knowledge. I think a lot of times, farmers know what they’re doing and are doing their best, but they haven’t seen anything else. If I haven’t seen something like that, it’s hard to imagine doing it differently. I know more people throughout the peninsula who organize groups and collectives of farmers to train and visit other farms, and I think that’s an essential part of this process.

We want to start offering more of that here—not just on our farm, but also visiting other farms in the Alvelal network or even further away.

Alpha: Are your trainings a couple of hours or multi-day? How do they look?

Sylvia: It’s usually a full morning, plus lunch. Lunch is a great time for people to connect and discuss in a more relaxed way. So it’s usually full mornings or full days, but not more than that because farmers are busy and can’t really spare multiple days.

Alpha: How far do they usually drive to come to your training?

Silvia: Most of them are quite close—maybe half an hour to one hour away.

Alpha: Did you have to promote these workshops and trainings quite a bit? How did you go about promoting them?

Silvia: Yeah, we’re promoting them. The trainings we’re currently offering are funded by EIT Food, a European program focused on training farmers in regenerative agriculture, based a bit on farmer-to-farmer training. We promote them on social media, old-school style by hanging flyers at the local bar, and we send messages through WhatsApp to people we know. Word of mouth usually helps, too.

Alpha: Okay, cool. I know Commonland came in at one point.

Silvia: I think Commonland came in at a moment when a lot of things were happening, and there was this vision of, “Maybe we should get together and give this a bit more shape.” That’s how I think Alvelal was born—from a few meetings among people already involved in regenerative agriculture and alternative farming systems.

We have 356 farms, 37,000 hectares positively influenced, 115 people who are members of this association, and 300 people supported by the Alvelal funds. They offer funds for water retention infrastructure, seeds, and other things over the past 10 years.

[projects of Alvelal, the little R’s are regenerative farms, from https://landscapes.global/partnership/alvelal/ ]

Alpha: And it’s not just farmers, right? It’s also local businesses that are kind of woven together.

Silvia: Exactly. A big part of what Alvelal started doing was promoting the creation of regenerative businesses. It’s not just about making sure that whatever you do—whether it’s ecosystem restoration or regenerative agriculture—has an economic return for your business, but also for the region.

So that’s a major focus. The cooperative was also born, mainly to sell regenerative almonds, but I think it’s expanding to more products now. There’s actually a whole network of satellite businesses that have arisen, probably inspired by the whole Alvelal network.

Alpha: So that's kind of cool. You have this whole farming thing, but you also have a co-op that’s funneling your produce out into the world. So, the middleman is part of your group, making it a lot more amenable to your needs.

Silvia: Yeah, what they managed to do at the beginning, which was great, is sell almonds for a better price, even though there’s no regenerative certification. You can’t certify as regenerative, but by bringing together different farmers, they managed to communicate effectively, showing that these farmers grow in a different way, that their products are worth more, and that they’re regenerating the landscape. I think that’s really interesting.

It’s an example of how you can promote better consumption and offer better products, even if it’s not under a specific certification, just by gathering people and being absolutely clear and transparent about what you're doing.

Alpha: So, the almonds are known to come from this area, right? It’s kind of like how champagne comes from a specific region in France, and certain cheeses are known for coming from particular places.

Silvia: Exactly. I think that would be beautiful. We’re thinking of having a branding so that anything that comes from this valley follows these principles. It may not necessarily be certified, but it means it’s supporting the local community, biodiversity, and soil health. I think creating this type of network helps consumers feel more connected because they know where their products come from. That’s why people are often willing to pay more—they feel a connection.

Alpha: Yeah, so this could be replicated in different regions in Spain too, right? Like maybe oil from this area?

Silvia: Well, hopefully a variety of products! We don’t want to end up with just monoculture. It would be nice to have some variety from any region—like almonds from here and olives from there.

Alpha: Right. And thats what this returns framework is that Commonland brought in? Those are the capitals of your local area, right?

Silvia: Yes, exactly. The focus is important because many restoration or alternative agriculture projects struggle when they only look at one aspect, like biodiversity or healthier production. The idea is that things only work when you consider the whole picture. So when we talk about natural capital returns, we're discussing nature, society, finances, and inspiration. That’s the part I find most appealing—it's not just about the impact within your community but also the impact you have outside of it, which is a huge strength.

The farms within Alvelal can also serve as inspiring places for visitors. Many farms are open to receiving visits. We always have people around, whether they're volunteers or participants in courses and training. I want people to come here, see what we're doing, and be inspired. I think that’s a crucial element of the whole framework; it encourages us to think beyond just our local area.

Alpha: When Commonland facilitated the process, they brought together multiple stakeholders to create a 20-year plan. People expressed a desire for their kids to want to stay in this area.

From that, you kind of agree on certain points, and while there might be sticking points, you at least have some common ground. Was the idea to gradually shift from more extractive industries to regenerative practices over this 20-year plan?

Silvia: Yeah, talking about future generations is super important. As we’ve started looking into our vision for the Valley, we’re thinking about what essential elements we need. If people here could reflect on a couple of generations back and a couple forward, I think it would completely change how they act and make decisions.

Alpha: Over the generations, there’s also been a noticeable loss of rain from the small water cycle, which is evident. We need to regenerate on a larger scale, but at least the rain that comes from that small water cycle of rapid transpiration should return over time.

Silvia: Yes, people tell us that there used to be snow throughout the winter. I’ve seen snow here; it does snow in winter, but not like it used to. In the last two years, it might snow for two weeks and that’s it.

There’s this place they used to call the lagoon because every year there would be water for many months after the rains. There are still people alive who remember this, so it’s not just some vague changing pattern. We want to work with this memory. Realizing that this memory exists and that people still remember how different things were is a strong way to communicate. It can help reconnect people with the reality that things are changing for the worse and that action is needed—like my mother remembers when things were really different.

Alpha: Snow is a more dramatic change because it’s obvious when there’s less or more snow. With rain, you have to calculate it, but snow is visible. Alvelal includes Granada, right? And Granada has the whole Sierra Nevada, which is experiencing the same issues with disappearing snow, right?

Silvia: Yes. Also in Italy and the north of Italy, people are really concerned about not having snow—not just for the water reserves but also because they can’t go skiing. The immediate concern is, “It’s December, and there’s no snow! What are we going to do?”

Alpha: Yeah, the lack of snow is obvious for the tourism or ski industry. But snow is also crucial for the water supply because it works within the whole slow water paradigm. It melts slowly, providing water later in the season, especially during the dry season. If it melts too early, there’s less water available for the dry months.

Silvia: Exactly. I can’t imagine how much the water cycle has changed here in the last ten years. I can tell because the springs are drying up a lot, which is massive. This area has good aquifers because it’s limestone, so it can hold a lot of water, but the changes are significant. If it rains a bit more, we get a bit more water, but it also dries up faster.

Alpha: How many of the farms in the region have switched over to more regenerative methods, would you say?

Silvia: Well, they say there are around 500 farms involved. It’s always hard to determine if a farm has truly switched. What does it mean to switch? If I start feeling less or make one change, am I switching? It’s a process. As we kick off this new project, our goal for next year is to engage at least three more farms in regenerative practices. The following year, we hope to add another three or four, creating a ripple effect. So we’ll have more to share next year!

…..

This is a reader supported publication

Share this post