I met Sieger Burger a few years back, and we have had quite a few interesting conversations about water over that time. He is a hydrologist and writer. In this conversation we range over many aspects of the water cycle, with a focus on hydraulic redistribution (how plants bring up groundwater), and foliar water upake (the process by which leafs can take in water).

During Sieger’s Dutch childhood, he became interested in water - “water was fascinating to me. Water is this weird molecule that is both bringing life and also bringing death. It's really about water—where the sweet spot is, of the right quality. Not too pure, because with water, we can't have distilled water. Also, not too salty or polluted. You need to have the right quantity, if you have not enough, then we dry out, and if it's too much, then we drown. It's this fascination with water as a life-giver.” [quotes in this essay have been slightly edited to remove conversational filler words]

Burger went to Delft University to study integrated water resources management. There he took a class from Hubert Savenije, and met Ruud Van der Ent, who was Savenije’s graduate student. Van der Ent and Savenije created a map of the small water cycle (precipitation recycling), showing where the evapotranspiration in one country, comes down as rain in another country. (The article on this map was the most read piece in this newsletter last year). Burger says of their work-

“I think that it is fascinating what their work has started. The whole concept of precipitationsheds was, more or less, based on Van der Ent's work [developed formally by Patrick Keys]. It shows where my precipitation comes from, you know, so that you get an understanding of the range of area where your rain has been evaporated. If you talk about having enough water, especially in drier areas, that's really useful to know because that helps you realize: if I am in Kenya, where does my water originate from? If I'm in Kazakhstan, where does my water originate from? If I'm in the Sahel, where does my water come from? I think that that work has really helped to get a much, much better understanding of the whole hydrologic cycle. And I think it also has made it possible to visualize things. One of my first lectures was ‘A picture tells more than a thousand words,’ and those pictures from Van der Ent and all the others have really helped tell that story of the small hydrologic cycle.”

As a hydrologist, Burger went to work in Uganda -

“Uganda - lots of people call it the paradise. Around Lake Victoria, where we were based, it was between 15 and 30 degrees. It's perfect growing conditions. Lake Victoria rehydrates the air so that you have very high rainfall. So everything grows.

But at the same time, more and more forests were cleared for growing large-scale annual crops. Then, if you get your tropical rains, all the soil can erode. I tried to encourage people to go into agroforestry. I was able to implement a few agroforestry projects to really showcase the combination of the design and plant growth. The fascinating thing about the tropics—things grow so quickly. So, with the right design, with a syntropic agroforestry system, you get after a year, the fast-growing pioneering trees at like four or five meters tall, from a seedling that was 15 centimeters. The soil comes alive, and you just create this life-giving ecosystem that is productive. We got cassava growing there, and the roots were massive, bigger than most people had ever seen. It's all about how you design it in order to give life—make growth possible so that water becomes a life-giver."

Curious about many aspects of the water cycle and ecosystem, Burger started a blog “A journey of discovery into the world of food, soil, and water”. ( Its in Dutch, but you can click the translate into English button.) On why he began a blog -

“I started a bit in Afghanistan. Afghanistan is a sad country because since '79, it's been in war. When I was there in 2011-2013, all the hills were denuded, all the trees were cut, all the grass was gone. And you just see terrible things environmentally happening because it's just a man-made desert. And that made me realize I just need to dive into how this works. When we moved back to the Netherlands, I got more into agriculture. Everyone was saying agriculture is causing lots of issues, like, what does that mean? What is it? You know? That made me first try to understand how this whole agricultural system works. It's a dive into the negatives, but you also need to have an alternative. And that where I started to dive into all the aspects that nature is providing, is giving us, and that we can use. That is where I got into all kinds of aspects of plants, of trees, of the biotic pump concept. It's all these things that just made me realize it's such a complex ecosystem altogether. It's really trying to get a much better rational picture—be able to tell the story much better. That's why I dived into it.”

On how plant leaves can drink in water vapor, in a process called foliar water uptake. Its a process that is for instance important in California, where redwoods get up to a third of their water from the fog which they ingest through foliar water uptake :

“Fascinating enough, if the plant becomes very dry, it appears that there are plants that can absorb water from the sky. It’s mostly water drops that are falling on the leaf. So it can be dew, it can be fog, it can be rainfall after a very dry period. At that point, the water pressure just becomes zero because there’s water available. So then the water can be sucked into the plant and is just filling up this gap of water shortage in the plant. According to one paper, we know this already for quite a long time, for a few hundred years. Now that we face more and more droughts and water becomes more scarce, we start to think, how on earth do we keep our plants and vegetation alive? Are there alternative water sources?

This foliar water uptake, as it’s called, is becoming an interesting alternative, especially if it’s then combined with hydrologic, hydraulic redistribution [plants bringing up groundwater] , as well as some plants can do. The drier it is, the more significant this will be. Foliar water uptake in certain redwood tree ecosystems has been measured as a third, and in the Negev Desert in the south of Israel, it was three quarters of their total water budget. In dry climates, this can be really significant. Orchids have a huge percentage because they have no roots, they are more or less largely depending on foliar water uptake. It has now been found in all climates—in tropics, in arids, in subtropics, Mediterranean—whatever climate there is, these plants have been identified to do foliar water uptake.

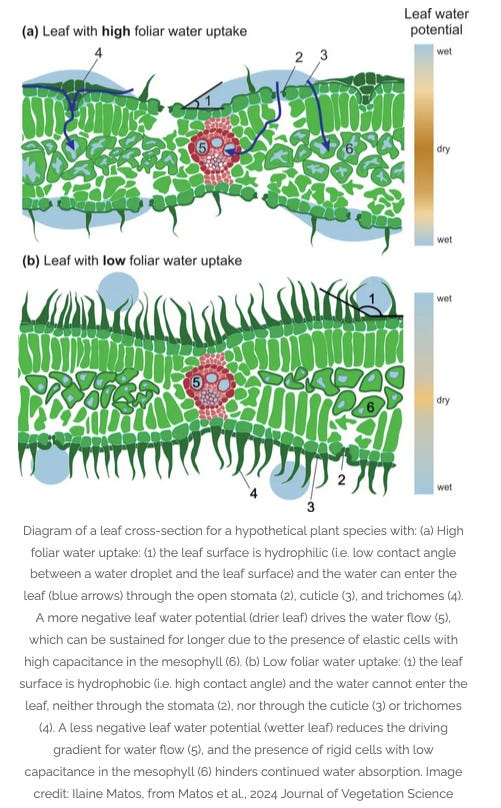

From Sieger’s blog article on foliar water uptake

“Because the process of water flow through the plant is driven by tension differences, water can also be absorbed in the leaves if the tension gradient is directed inwards. This can occur when it starts to rain after a very long dry period (see image below). The tension in the air becomes 0 MPa, while in the soil it is still around -1 MPa and in the plant around -2 MPa or higher values. When it starts to rain, the leaves are the first to get wet, while in the plant/tree and in the soil there is still a high suction tension. Water can be absorbed via the leaves and reduce the suction tension in the plant/tree. The longer it rains, the further downwards the water can be sucked (the flow direction then completely reverses). At such times, water can even go from the leaves to the roots and ultimately infiltrate into the soil.

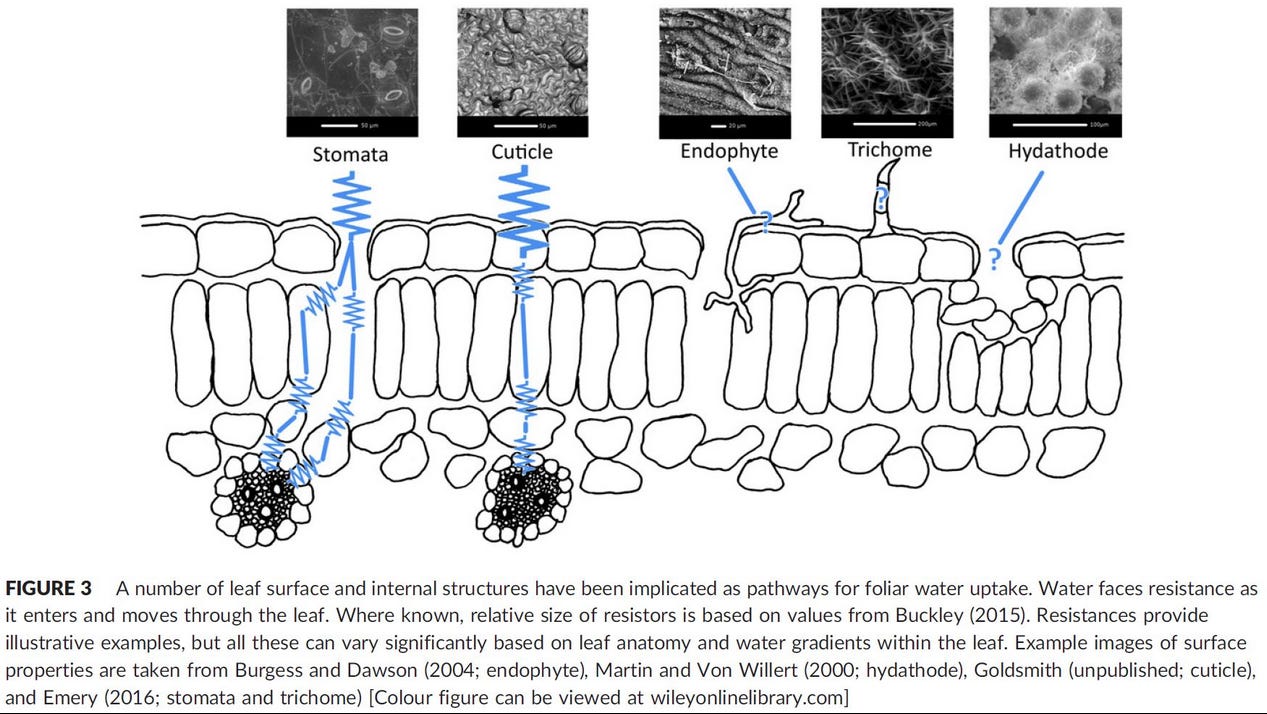

In the last 20 years has much more research been done into Foliar Water Uptake and more insight has been gained. The consequence of this, however, is that many processes have mainly been described as possibilities, but have not yet been sufficiently studied. The research into Foliar Water Uptake has therefore not yet provided any clarity on how exactly the process works, and especially, how the water enters the plant from outside. It is clear that the water enters the plant based on voltage differences (hence the dive into the depths on voltage differences at the beginning of the blog post), but where exactly that happens is not yet clear at this time.

Foliar Water Uptale has already been found in more than 233 species, spread over 77 plant families in 6 different biomes… it seems to occur everywhere.

This study used shows 5 possible locations where water enters the plant:

through the stomata

through the top layer or cuticle of the plant (cuticle)

via the endophytes (endophyte)

via the hair or trichome of the plant (trichome)

through the water pores of the plant (hydathode)

On the complexity of the water cycle and how vegetation supports it:

“Just the amount of feedback systems, feedback loops, and buffers, and everything that’s in there—it’s just mind-blowing, yeah. And that it is also the whole thing that also makes this planet stable and allows it to receive water everywhere, you know? All these recycling loops make sure that water is brought to say China, because it’s just recycled, recycled, recycled. That’s what keeps this planet alive! We should nurture that. We should make sure that keeps happening, you know? If we all end up with extreme weather everywhere, and you end up with a flood every autumn and 40–50 degrees Celsius every summer, then it becomes uninhabitable. Vegetation can do a lot, to mitigate that at least.”

On floods and droughts :

“What most people don’t realize—floods and droughts are brothers and sisters, you know? They often come together. And people ask, “What? Do they come together?” If you have a flash flood, all the water is gone afterward, and then you end up with a drought. And because you have a drought, there’s no water, so the soil starts closing up—it clogs, it hardens, and soil life begins to die. So you just get this hard crust on the surface. If you then get new rainfall, it’s even worse! Then you get into this downward spiral of a dying landscape. And a dying landscape becomes even hotter, making it even more unbearable. We need to get the water back in order to create a much more pleasant environment to live in.

Milan Milan is saying, more or less showing, that the landscape has changed so strongly that the summer rains have disappeared. On the other side of the coin the forests have all disappeared, the soil sponge has disappeared. So then you get these massive floods that’s caused by the removal of the forests, in combination with the heating, which creates more extreme rainfall, extreme weather, higher temperatures, more water in the air, all that kind of thing as well.

It’s a complex system. It’s not like you can point at one factor, but the sponge in the landscape in a lot of places has been removed. And when the sponge is gone, then you get flash floods and droughts.”

On biological matter nucleating rain :

“The pollen, the fungal spores, and the bacteria are needed for cloud formation. There is this lovely paper putting together all data on cloud freezing nuclei and the temperature at which they freeze water. Biological freezing happens at much, much higher temperatures than chemical or mineral freezing. Forests creates all kinds of cloud freezing nuclei, which allows rainfall to happen at a higher temperature.

In high school I learned that water freezes at zero degrees, you know? That’s what everyone knows. That’s how we calibrate thermometers. Freezing water is zero. That’s high school physics. Well, if you have pure water, it freezes at minus 40. I mean, I was like, "What? Why did no one tell me that before?" What? Pure water freezes at minus 40?

Biology is able to create freezing at very high temperatures, like minus three to minus 15 Celsius roughly. But a lot of the mineralogical and chemical particles that cause freezing are more in the spectrum of minus 15 to minus 30 Celsius.”

References

Berry, Z. Carter, Nathan C. Emery, Sybil G. Gotsch, and Gregory R. Goldsmith. "Foliar water uptake: processes, pathways, and integration into plant water budgets." Plant, cell & environment 42, no. 2 (2019): 410-423

Limm, Emily Burns, Kevin A. Simonin, Aron G. Bothman, and Todd E. Dawson. "Foliar water uptake: a common water acquisition strategy for plants of the redwood forest." Oecologia 161 (2009): 449-459

Share this post