Taming the hot dry winds that cause wildfires; sponging up freak storms

a California and Nevada rethinking

The recent fires in Los Angeles can be traced back to the Great Basin. The Great Basin is a vast area sandwiched between the Sierra Nevada’s and Cascade mountains to the west, and the Rocky Mountains to the east, and is centered in Nevada, California’s neighboring state. The Great Basin is the source of the strong, hot, dry winds, that blew southwards into Los Angeles and fanned the flames there.

These winds are called the Santa Ana’s. Joan Didion wrote about the Santa Ana’s for the Saturday Evening Post back in 1967. “There is something uneasy in the Los Angeles air this afternoon, some unnatural stillness, some tension. What it means is that tonight a Santa Ana will begin to blow, a hot wind from the northeast whining down through the Cajon and San Gorgonio Passes, blowing up sand storms out along Route 66, drying the hills and the nerves to flash point. For a few days now we will see smoke back in the canyons, and hear sirens in the night. I have neither heard nor read that a Santa Ana is due, but I know it, and almost everyone I have seen today knows it too. We know it because we feel it. The baby frets. The maid sulks. I rekindle a waning argument with the telephone company, then cut my losses and lie down, given over to whatever it is in the air. “

The Santa Ana’s, already strong, hot and dry, have been getting even stronger, hotter and drier, over the past few decades. The winds that caused the fires in LA reached 99 mph.

In 1990, nine million hectares of the Great Basin was uninhabited, by 2004 only 1.2 million hectares was uninhabited. The influx of people has led to the draining of the aquifers. Groundwater is usually brought up by the vegetation to help cool the landscape. If the air is cooler and more humid in the Great Basin, then it will be cooler and more humid by the time it blows into LA. Groundwater is Gaia’s sweat glands. If we drain the groundwater though, the land gets hotter and drier, and the winds get hotter and drier, which means they are more likely to initiate wildfires.

In recent years Native American tribes, locals, and environmentalists have fought off the building of a pipeline to drain even more of the aquifers, to supply to the big cities like Las Vegas.

The Great Basin has also been losing its vegetation. It has been experiencing more wildfire because of the invasive cheatgrass that was brought in to the area. And the Great Basin is suffering from the lessening of the snow in the Sierra Nevada mountains, which has impacted the amount of melted hydration the area gets.

As the Santa Ana wind blows southward from the Great Basin, parts of it will go through the Owen’s Valley area. This area used to have a large flowing river, lined with trees, that flowed into Owens Lake, a lake that spanned 280 square kilometers (28000 hectares). There used to be so many birds in the area that they would black out the sky.

[from Owenvalleyhistory.com]

But then in 1913, William Mulholland stole the water from the area, in a process/fight famously chronicled in the book Cadillac Desert, and in the movie Chinatown. He built an aqueduct to pipe the water to the growing LA area. That dried up the Owen’s Valley area and shrunk the lake to a thin mirror of what it used to be.

So now when the Santa Ana’s blow through, there are not trees to slow it down, nor is there much transpiration to add moisture to it.

The Santa Ana’s then blow across the Mojave desert. The Mojave too has been draining its groundwater, which means the vegetation cannot bring it up water and use it to cool off the land as much. So the Mojave land heats up the Santa Ana’s even more.

[wind map on Jan 7, 2025, the first day of LA fires. from Ventusky.com ]

As the Santa Ana’s get nearer LA they can get slowed by the forests in the San Bernadino Mountains to the northeast of LA. However these forests there have been thinned by timber industries in the 1800s and 1900s, and more recently, by numerous big fires. Now they provide less windbreak. So the Santa Ana winds are stronger. As California loses more of its forests many things get more difficult.

…

The Great Basin is also the source of the Diablo winds, which blow over the Sierra Nevada mountain range into Northern California, causing a lot of wildfires there.

Humans have destroyed a lot of the virgin forests in the Sierra Nevada mountain range. In the pictures below the black areas and black dots are virgin forests. The black leg in the diagram, is the Sierra Nevada mountain range that extends down the middle of California . This first picture is of the forest landscape in 1850.

This next picture is in 1920, where each dot represents 25,000 acres of virgin forests.

This is the picture today. Only a few large virgin forests remain.

Chad Hanson, Curtis Bradley, Dominick Dellasalla performed a research study where they examined 1500 fires in the Western USA. They found that virgin, unmanaged forests were best at stopping wildfire - “forests with the highest levels of protection from logging tend to burn least severely.” Unmanaged, virgin forests have their own cooling and humidifying system. Dead logs and underbrush can absorb a lot of water. So when fires hit these areas, they have a much harder burning. These also better humidify the winds blowing over them. To the researchers their results “suggest[s] a need for managers and policymakers to rethink current forest and fire management direction, particularly proposals that seek to weaken forest protections or suspend environmental laws ostensibly to facilitate a more extensive and industrial forest–fire management regime” [Bradley 2016]. Chad Hanson has written a book called Smokescreen about this topic.

There were huge rains in California in the early part of 2024. Unmanaged forests would be better able to keep some that water in the ecosystem into 2025, and used them used that water to humidify Santa Ana and Diablo winds.

Unmanaged virgin forests are not just useful in California to lessen wildfires. In the boreal forests of Russia, the unmanaged and unlogged forests there have much less wildfire than the logged ones, notes climate researcher and physicist Anastasia Makarieva.

For fire prevention purposes, hydration is also needed on the western side of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, in the more populous parts of California.

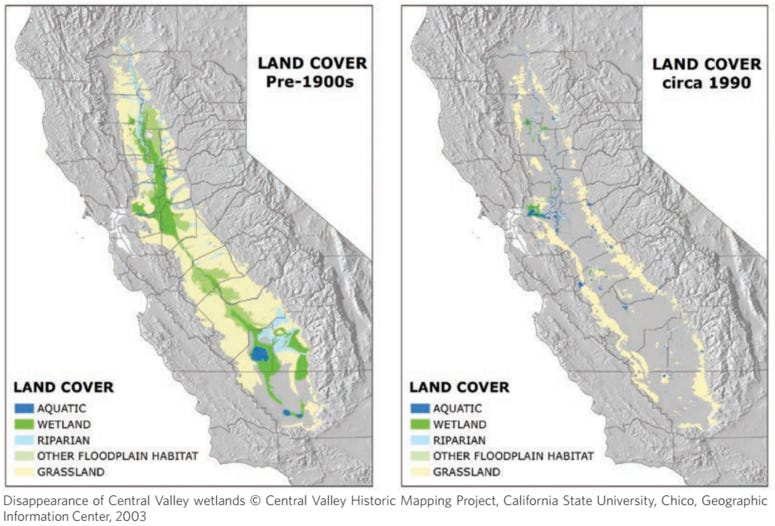

The Central Valley area in California has drained its wetlands for agriculture. Before 1900 the valley was made up of about a quarter wetlands. Tulare Lake, spanning 1800 square kilometers lay there. These wetlands humidified the winds, and created precipitation recycling. Its evaporation added ocean moisture blowing in to create rains in the summer, and the snow in the winter, which can affect both California and the Great Basin.

Its possible to bring some of these wetlands back. During the huge rains of 2022, the area that used to be Tulare Lake actually filled up again with water to a significant amount. However, because there were so many land developments in the lake bed, the lake was drained again.

Hydration for California also comes from the fog that rolls of the coast of California. The atmospheric scientist Millan Millan noted this was an important source of hydration for California. Redwoods drink the fog. However as more and more coastal land has become developed, the ensuing urban heating has destroyed a significant portion of the fog.

When we look closely at phenomena in the environment, we will often find that they are all connected. In this case, the coastal fog, the wetlands of California, the hydration and land-use of the Great Basin, the land use of the Mojave, the logging and managment of Californian forests; it all connects and ties into the severity of the Californian wildfires.

California is caught in a vicious cycle of drought, fire and floods, in what Zach Weiss and Water Stories calls the watershed death spiral. With each natural disaster the forests reduce in size and number, which then leads to bigger, drier winds, which leads to bigger fires. Less forests, means less precipitation recycling which means more prolonged drought. California needs its forests to manage its wind patterns and its precipitation recycling. It needs its groundwater so the trees have something to tap into in the dry season. It needs it rivers undammed so the large rains can overflow into the floodplains and deposit the sediment, grow the ecosystem, and fill up the aquifers. It needs vast amounts of land to be ecorestored. It is in danger of going the way of the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East, when desertification followed human mismanagement, or of going the way of the the African Sahel in the mid 1900s, when desertification followed the chopping down of trees.

California has been in part surviving by pumping water from the Colorado River. But that is putting that river in danger of collapsing in the decades ahead, which will be catastrophic to the whole US southwest.

California and Nevada need to do some deep thinking about what matters. The hole its digging itself into keeps getting bigger and bigger. It cannot keep supporting more people to move to the area. It cannot support its water intensive agriculture. The states need to change their land-use patterns. It needs to undevelop built on land, and return it to its previous nature. California and Nevada need to undergo some massive paradigm shifts in thinking, before its too late.

China woke up their land degradation practices that led to massive floods that displaced millions of people. They realized they had to turn residential land and business land back to floodplains and wetlands. They had to adopt a sponge city, and sponge nation attitude.

There are ways out of this Californian mess. We could see the huge rains that California has gotten in recent years, and will probably get more of in the form of freak storms in the future, as latent gifts from Nature. But they will really only become gifts if we allow the land to be a sponge, and absorb and hold the rains. That will require restoring the soil, forests, and wetlands of the Golden State. That will then in turn tame the hot dry winds that cause wildfires.

Bradley, Curtis M., Chad T. Hanson, and Dominick A. DellaSala. "Does increased forest protection correspond to higher fire severity in frequent‐fire forests of the western United States?." Ecosphere 7, no. 10 (2016): e01492

Lovely post Alpha. Two things: In the context of sponges, one of my favorite sound bites when talking to farmers is that "There is no point in praying for rain, unless you give God somewhere to put it". i.e. a soil that can receive it. Storing water in the soil is the best place for it because, as you say, it keeps everything hydrated. The second point is that when we discuss groundwater, I believe it is a similar situation faced by fisheries that have learned that, if you protect between 1/4 and 1/3 of a fishery as a breeding reserve, everyone catches more fish. I believe the same thing could be shown for groundwater. If we, as a society, allow the groundwater back to a level where it helps hydrate the vegetation (say within 20m of the soil surface) then we will all get better rainfall/snowfall and we will ALL have more freshwater to use. Bruce Danckwerts, CHOMA, Zambia

Excellent post, Alpha. I like how you bring in ground water. I don't think people realize the importance of ground water. It's been portrayed as something deep underground which kind of just sits there, rather than being actively involved in above-ground moisture.

There is also the issue of massive solar arrays which lie directly in the path of the Santa Ana winds, heating the air above them by up to 7F. This, as reported by Natalie Flemming, of Ecosystem Restoration Alliance. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/los-angeles-ablaze-tragic-solar-array-wake-up-call-natalie-fleming-4zhnc/